The NHS is failing Scotland’s new mums & babies by sidelining dads, according to evidence from our survey of new fathers.

The NHS is failing Scotland’s new mums & babies by sidelining dads, according to evidence from our survey of new fathers.

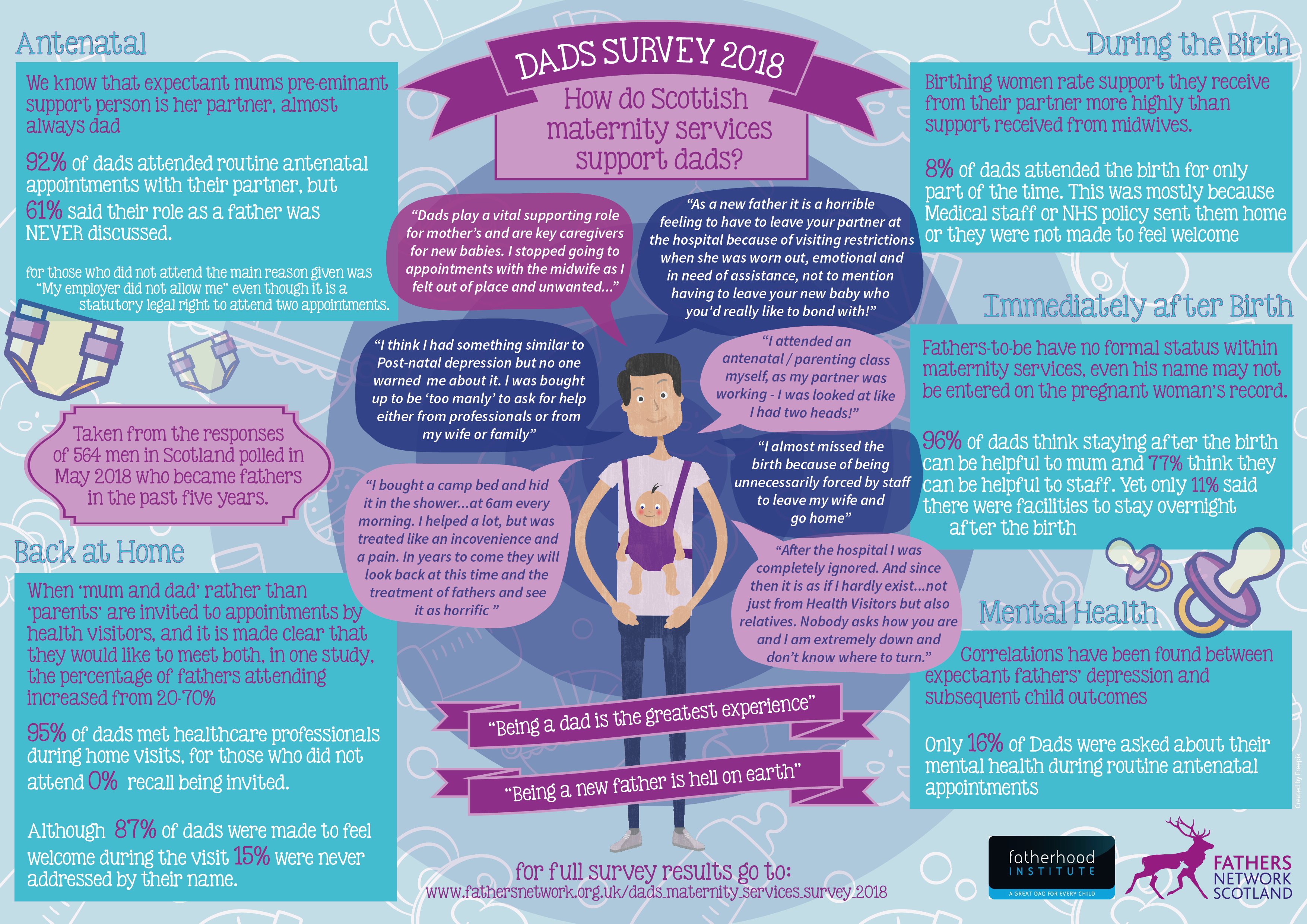

More than 560 of you in Scotland, and 1800 across the UK, responded to the survey of new dads' experience of antenatal, birth or health visitor services - and the results indicate that the NHS is failing to provide the ‘family-centred’ services required by its own rules* and desired by parents.

Although almost all of the new fathers were present in maternity services at each stage , the survey jointly undertaken by Fathers Network Scotland and the Fatherhood Institute shows that large numbers felt ignored before, during, and after delivery, even though their involvement is central to infant and maternal well-being and is desired by mothers.

Mixed policy messages

Many spoke of outdated visiting policies and inadequate or non-existent overnight facilities for dads, adding stress to an already emotionally-heightened time - even though UK NHS policy since 2004 requires maternity services to deliver ‘mother-focused and family centred’ care.

In Scotland, the Best Start maternity plan (2017) stipulates: "All mothers and babies are offered a truly family-centred, safe and compassionate approach to their care... Fathers, partners and other family members are actively encouraged and supported to become an integral part of all aspects of care.”

Pregnant and birthing women typically want their partner with them not only because he is their closest companion but also because he provides continuity of care and support amid stretched NHS services, according to a major new report published by our colleagues at the Fatherhood Institute to coincide with the survey in the run-up to Father's Day.

Funded by the Nuffield Foundation, Who’s the bloke in the room? - a review of UK evidence about new fathers and health services - details how expectant fathers in Britain are key influences on maternal and infant health and well-being , including on pregnant women’s smoking, diet, physical activity and mental health, and on children’s later development.

It recommends specific new measures to welcome fathers throughout pregnancy, birth and early infancy (see bottom of this article or here) reinforced by what you told us in the survey How was it for you? Read full Scottish results here or as infogram; UK results here or our Scottish/UK summary below:

Antenatal Services

- 65% (61% in Scotland) said antenatal healthcare professionals had rarely or never discussed fathers’ roles.

- Half (56% UK; 50% Scotland) had rarely or never been addressed by name.

- Fewer than a quarter had been asked about their physical health (22% UK; 24.5% Scotland) or diet and exercise (18% UK; 20.9% Scotland).

- 48% in both UK and Scotland) had not been asked about smoking, despite the risks of passive smoking to babies, and fathers’ key role in supporting pregnant mums to give up.

- And even though a father’s mental health is closely correlated with a mother’s, only 18% (16% in Scotland) had been questioned about it.

Birth Experience

While two thirds of fathers said they felt welcome at their children’s birth, the poll records high levels of disappointment in hospital policy, particularly in Scotland, where nearly half of fathers (48% in Scotland compared to 40% in UK) said that hospitals had not allowed sufficient time for the new family to spend together after the birth.

Qualitative feedback included reports of fathers missing crucial moments of bonding following their children’s births, and feeling sidelined despite their partners’ desire for support. Only 1 in 10 dads polled in Scotland (compared to 17% in UK) reported that their hospital had facilities for fathers to stay overnight afterwards, even though the then Prime Minister Gordon Brown called eight years ago for hospitals to provide such facilities.

In Scotland 96% of dads felt staying after the birth would be helpful to mum, and 77% believe they can be helpful to staff, who are often overstretched.

However there were also encouraging signs of change, with Dundee’s Ninewells Hospital, Edinburgh Royal Infirmary, Arbroath Infirmary each singled out for praise in qualitative feedback. Crosshouse Hospital in Kilmarnock was named by one respondent as “very welcoming and inclusive” of dads.

Postnatal Care

Nearly half of the dads surveyed said that their role was rarely or never spoken about at home visits (47% in Scotland), even though dads’ influence infant feeding and are key to spotting maternal depression.

Many also reported their own struggles with mental health, with no signposting for support for dads, despite evidence of paternal susceptibility to depression following birth. (continued below...)

Samantha Pringle, director of Fathers Network Scotland, said: “All the research shows that involving fathers at this crucial time of preparation, birth and post-natal care has a positive impact on the whole family. But our survey sadly shows that fathers remain an under-used resource at a time when a stretched NHS would most benefit from the support they bring to their families.

Samantha Pringle, director of Fathers Network Scotland, said: “All the research shows that involving fathers at this crucial time of preparation, birth and post-natal care has a positive impact on the whole family. But our survey sadly shows that fathers remain an under-used resource at a time when a stretched NHS would most benefit from the support they bring to their families.

"Let’s change this outdated attitude and follow the beacons of excellent practice - such as the Dads2B classes pioneered across the Lothians. They show how instilling confidence in expectant fathers can ripple through the whole community.”

Adrienne Burgess, Co-Chief Executive of the Fatherhood Institute said: “Our survey shows that dads are there for mums every step of the way – at routine antenatal appointments, for the scan, labour, birth and back home. No-one can say dads are not interested or unwilling. But the survey reveals serious failings in the NHS approach at every stage.

"Too often, services are ignoring fathers, in spite of dads’ importance to healthy pregnancies and babies and even though mothers want their partner to be involved and informed."

Pioneering Change

Here at Father's Network Scotland we're working with trailblazers across Scotland bringing dad-friendly best practice into health and family services with the help of our Understanding Dad programme, currently rolling out across the country.

We're also backing the recommendations of Who’s the bloke in the room? which calls for a more family-centred service that enrols expectant fathers in maternity services from ‘booking in’, records and responds to their health needs and behaviours, and which trains maternity staff to engage with them.

The recommendations are all about making fathers welcome throughout pregnancy, birth and early infancy, and valuing the role they play not just as supportive partners but also as independent parents with a unique connection to their baby.

We want to see the NHS to include expectant and new fathers at all stages and inform them as thoroughly as it currently informs pregnant women and new mothers:

Key Recommendations from Nuffield Report

1: Change NHS terminology to refer to fathers

At the time of the birth, 95% of parents are in a couple relationship, and 95% register the birth together. For a woman to have a new partner at this stage is almost unheard-of; and only one birth in a thousand is registered to two women. Yet despite the overwhelming presence of the biological father, the term ‘woman’s partner’ or ‘mother’s partner’ (rather than ‘father’) is commonly used in maternity services. This defines the baby’s father solely as a support-person and does not recognise his unique connections (both genetic and social) to his infant. The term ‘woman’s partner’ should be widely replaced by ‘father/ woman’s partner’.

2: Invite, enrol and engage with expectant dads

Employed fathers in Britain have a statutory right to time off to attend two antenatal appointments. Each father (or woman’s partner) should (with the pregnant woman’s consent) be formally enrolled in maternity services and an official invitation to meet the maternity team issued. This will acknowledge the father as a parent as well as a support-person, and provide a pathway to welcoming, educating and informing him, identifying strengths and challenges associated with him, and referring him to relevant services (e.g. to smoking cessation). Working groups in each of the four countries in the UK should be established to consider mechanisms for enrolling the father/ woman’s partner; and to identify potential pilot sites.

3: Deliver woman-focused, family-centred services

Expectant fathers’ direct impact on the mother and indirect impact on the unborn child, are significant. Maternity services should be formulated as ‘woman-focused and family-centred’ meaning that, while the obstetrics focus remains on the pregnant woman, the father (or, where relevant, woman’s partner and other key supporters) are actively encouraged to become an integral part of all aspects of maternal and newborn care. Hospitals should collect information from both parents about their experiences of family-centred care, as part of the NHS Friends and Family Test. Working groups in each of the four countries in the UK should be established to define family-centred care during pregnancy, at the birth and in neonatal care; and to explore strategies, objectives and targets for implementation – including providing facilities for fathers to stay overnight after the birth.

4: ‘Father-proof’ maternity staff training

The term ‘midwife’ means ‘with woman’ and most practitioners in maternity and neonatal care services are not trained to engage effectively with men or to work in a ‘partnership of care’ with families. When guidelines for maternal and neonatal care are drawn up, these should include the evidence on the impacts of fathers’ characteristics and behaviours on mother and infant; impacts of couple relationship functioning; and impacts of fatherhood on men.

Pre- and post- registration training curricula should be revised to include the ‘whys’ and ‘hows’ of engaging with fathers and families. When core competencies are time-tabled for revision, relevant new competencies should be drafted and included. Existing training modules (such as the NCSCT module on smoking in pregnancy) should be revised to equip healthcare practitioners to engage with both parents, rather than only with the woman.

5: ‘Father-proof’ information for expectant and new parents

Pre-natal health education and information should be directed at men as well as women, and maternity services should be required to provide information directly to the father/ woman’s partner, rather than relying on the ‘woman as educator’. To counter unconscious bias against men/ fathers as competent caregivers, the content should include the neurobiology of active fathering, co-operative caregiving (the ‘parenting team’) and the impacts of father involvement and couple functioning on the infant’s health and development. ‘Father-proofing’ guidelines to equip authors of new resources (and of resources that are being revised) to address both parents effectively should be developed and made available to commissioners, authors and editors, with the requirement that these be applied and utilized as part of the Gender Equality Impact Assessment.

6: Collect better data on expectant and new dads

On the basis of our research review, and a recent independent Longitudinal Studies Strategic review, we recommend that any future ‘birth’ cohort study should collect data in pregnancy from both the father/ woman’s partner and the mother (cohabiting or living separately), with a phase of testing for approaches to recruitment.

Where we have identified gaps in primary research and/ or in secondary analyses of data already collected, consideration should be given to commissioning primary research or secondary analysis of existing cohort data.

At birth registration, the father should be asked whether the infant being registered is his first child. Analysis of the data collected will then be able to establish fathers’ age at birth of first child and men’s fertility rates in Britain.

Read How was it for you? Scottish survey figures

Read How was if for you? UK survey figures

Read Who’s the bloke in the room? report

*Read The Best Start: A Five-Year Forward Plan for Maternity and Neonatal Care in Scotland published by the Scottish Government in 2017.